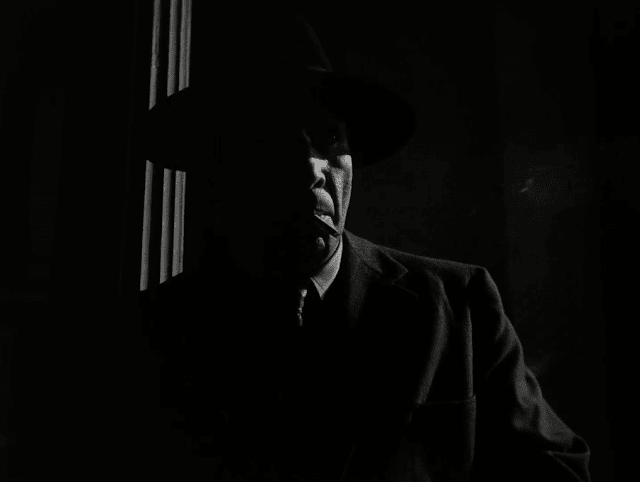

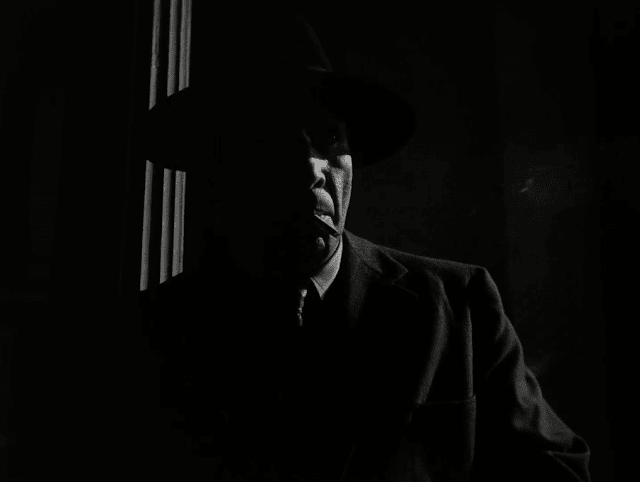

Throughout American serial crime and noir and psychological melodrama and robbery and revenge thriller films of the 1940s and 1950s, smoking became a symbol of existential despair, a psychological and emotional crutch used to prop up a character's mortal showing, an ambient prop, a burning menace, just simply an extension of hot and cancerous pain, jacketed in the reflective silo of the slim white tune, the mini phallic and the cool expression of one's doubting humanity. Smoking and noir have much to inform each other of.

Murder Can Be Bad For Ya Health

Smoking Kills

PAGE IN PROGRESS

They all smoke, every last one of them, only the oddest of odd psychopaths does not smoke, because they all smoke, top to bottom. Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), the hard-boiled insurance man in Billy Wilder's Double Indemnity (1944), the most famous film noir of all time, who takes deep drags on his cigarette, like everyone else having a thought or having a moment or making a decision in film noir, with tar and nicotine while giving their retrospective voice-over account, their so-called confession, of the murder plot in which they have became ensnared, in Neff's case at least. Neff's smoking is a poignant element reminder facet and burning prop that underscores his internal turmoil and sense of doom.

|

| Loretta Young in The Accused (1949) |

In Double Indemnity, Neff is flanked and backed up by two other noteworthy screen smokers: the platinum blonde, cigarette-toting cursing lovely legged mean minded husband harrying femme fatale of the oldest repute of all Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck), a woman whose sexual mystique combines the noir staples of power and deception; and Neff's man’s-man supervisor, Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), who seems unable to pass a moment of the day without a cigar, and does pass off no moment of any day without one, noting up another essential prop in noir, even if he does not always have a light.

Smoking, for these characters, is more than a habit—it is a signal of their inner conflicts and the murky moral landscapes they navigate. This is the biggest film in film noir and yet smoking is fully integrated into the style, there may be no smokeless noir.

.png) |

| Barry Sullivan lights up in The Miami Story (1954) |

Many of the great Hollywood film noir pictures were directed by émigré filmmakers such as Fritz Lang, Billy Wilder, Otto Preminger, Robert Siodmak, and Edgar G. Ulmer, who had honed their vision amidst the chiaroscuro lighting and rich, smoky shadows of German cinema in the 1920s. Their background in German Expressionism deeply influenced the visual and thematic style of American noir, where smoking became an integral part of the mise-en-scène. Smoke does come into this, in the most absolute of manners. The smoke of grenades and cigars, of swamps and city drains.

One of the rawest examples of film noir, deeply indebted to its Weimar antecedents, is Ulmer’s Detour (1945), an extremely low-budget picture contracted by a poverty-row studio, Producers Releasing Corporation (PRC), and shot in less than a week. Like Wilder in Double Indemnity, Ulmer employs voice-over narration from his distraught protagonist, Al Roberts (Tom Neal). Roberts, like Neff, is driven to murder and ultimately to confront his ghastly misfortune while the swirling smoke and ashes from his cigarette evaporate into the night.

Before his luck turns, Roberts is portrayed as a passionate artist, a classically trained pianist in a New York jazz club, who exhibits the talent for making it big someday. In an after-hours scene at the club, he takes deep, confident drags on a cigarette dangling from his mouth while banging on the piano keys in frenzied improvisation.

.png) |

| Ubiquitous American glamour smoking and women in advertising in Vicki (1953) |

However, on his ill-fated journey to reunite with his love, Sue (Claudia Drake), he becomes an accessory in the death of a motorist who gives him a lift and later finds himself ensnared by a treacherous vamp named Vera (Ann Savage). Vera, who had been traveling with the same motorist, holds her precious information about his untimely end over Roberts to keep him under her control. Vera, with her rapid-fire scurrilous prattle and reckless drinking, smokes with abandon, embodying the quintessential femme fatale's dangerous allure.

.png) |

| Howard Duff and Barry Kelley droopy cigar loser in Women's Prison (1955) |

In a cheap hotel room, trying to figure a way out of their misery, Al and Vera live in a sordid world where the cigarette butts in an overflowing ashtray and empty liquor bottles form a social tableau. Smoking, in Detour, is so essential to the film’s overall design and mood that the publicity materials depicted both figures leaning against a city lamp post with cigarettes in their hands.

The style of smoking cultivated in Weimar cinema and later in Hollywood noir—and indeed in a host of other eras and genres—can still be discerned in contemporary pictures. Most notable in this vein are the neo-noirs, many of which have appeared in recent years with conspicuous smokers occupying center frame. Joel and Ethan Coen’s The Man Who Wasn't There (2001), a retro existential drama shot in luscious black and white, features Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a simple barber who, like Walter Neff or Al Roberts, is tormented and introspective, given to deep cravings for tobacco. Thornton’s co-star Frances McDormand remarked, “All Thornton’s character does on screen is smoke and breathe,” highlighting how these simple actions set the tone for this sharp throwback to film noir.

|

| Peggy Dow lights Stephen McNally in Woman in Hiding (1950) |

There is mounting evidence that the Coen brothers are not alone. A recent piece in the New York Times, focusing on the apparent revival of cinematic smoking after 1990—up to which point smoking in movies had reportedly been on the wane—termed the new (and old) phenomenon: "Lights! Camera! Cigarettes!" Another reporter, writing in the Seattle Times, described Hollywood's recurrent obsession plainly: "Smoking is still very, very cool, and very, very sexy." Despite fierce opposition and negative medical studies, smoking on screen continues to fascinate and allure spectators. It remains a vital prop and cultural icon, a fundamental device for romance and rebellion, introspection and conviviality.

.png)

.png) |

| Smoking perfection but what is suggested by Valerie Hobson and Conrad Veidt in The Spy in Black (1939) |

The Spy in Black is driven entirely by Conrad Veidt, who delivers a strong performance, even two decades after his role in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. The supporting cast, including Sebastian Shaw as Ashington and Valerie Hobson as the schoolmistress-turned-spy, are equally effective. Cyril Raymond stands out as a nosy country parson who becomes too curious for his own good.

Historically, in times of war and peace, cinema has served as cultural escapism, transporting audiences to worlds where beauty, intrigue, fantasy, and imagination triumph over mortality concerns. The persistence of smoking in film noir and beyond underscores its enduring power to evoke complex emotional landscapes and character depth. It is unlikely that this significant symbol will vanish from our screens anytime soon.

.png) |

| Power-lighting the cigar with Barry Kelley and Warren Stevens in Women's Prison (1955) |

If smoking allows for the placement of match books as attractive and alluring clues for gumshoes, and detectives alike, the possibilities afforded to smoking the clues in a mystery are dramatically heightened, to even pull a kind of noirish comedy from any scene, almost as if one burns the evidence as one solves the crime, and the curative mental powers of tobacco smoke can be physical demonstrated as superior forensic mode of mastering the mystery.

.png) |

| Matchbook noir in I Was a Shoplifter (1951) |

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png) |

Smoking clues and cues for thought in film noir

Larry Keating in I Was A Shoplifter (1951)

.png) | | Classic clue on match-book in Armored Car Robbery (1950) |

Lighting up the scene of the crime is as essential to the screen as it is the theatre itself, and one could not consider smoking as an act of noir without the smoke absolutely leeching magically between the theatre, where everyone was smoking, and the screen, where the smoke becomes detoxified, purified in silver, is lunged back and fore between the two, with no real distinction in the murky light as to where the world ends and the fantasy begins. The smoke so blurs this.

The smoking variations of noir are one of the few glowing markers of film in the darkness, fumes des noir here en camion, in the bar or in the bedroom is one thing but en camion we can admire so many new moves. Here is the pipe lights a cigarette from The Thirteenth Hour (1947)

| Male bonding with cigarettes and pipe in truck noir The Thirteenth Hour (1947) |

Driver lights pipe in The Thirteenth Hour (1947)

Pipe lights cigarette in The Thirteenth Hour (1947)

Smokin' smug in The Thirteenth Hour (1947)

The Thirteenth Hour (1947) |

The first half of the 20th century marked the golden age of the cigarette, with around half the population of industrialized nations smoking by 1950. In countries like the United Kingdom, up to 80 percent of adult men were regular smokers.

From the 1920s to the 1950s, tobacco companies and film studios collaborated closely, placing products on screen and paying stars to endorse cigarettes. For nearly a decade, two out of three top movie stars, including icons like Bette Davis, John Wayne, and Humphrey Bogart, smoked specific brands in movies, making smoking seem glamorous and sophisticated.

.png) |

| "My pipe was drawing well . . . " Michael Duane in The Return of The Whistler (1948) |

In every scene with Claude Rains as Captain Renault in Casablanca (1942) you will see him smoking, lighting a cigarette or chain smoking. Claude Rains never smoked in real life. If you watch closely, you will notice he doesn’t inhale. Just pulls in to light and exhales immediately through his mouth.

The actors smoked in movies because they smoked in real life, not for product placement or to brainwash people into smoking. Smoking was prevalent as about 60% of Americans and 80% of Europeans smoked in the 1940s. This habit naturally appeared in scripts and stage directions, like “He lights a cigarette, paces, then turns to face her,” and was included by directors. This was a reflection of the times, except in Germany, where the Nazis largely banned smoking.

SOMETIMES SMOKES ARE THE ONLY THING

Sometimes it becomes apparent that there are so few props for the people of the old times that when it comes to mating the cigarette is all there to bring you together, casually. Cigarette secution is a thing, and in film noir, de rigeuer in nor, les smokes ces sont de rigeuer en noir.

.png) |

| Cigarette seduction with Beverly Michaels and Allan Nixon in Pickup (1951) |

Advances in technology allowed for mass production of cigarettes, while advertising continued to glamorize smoking. During both World Wars, the military distributed free cigarettes to soldiers, further normalizing the habit. Despite emerging links between smoking and lung cancer in the late 1940s and 1950s, cigarette use surged through the 1950s, embedding itself deeply in popular culture.

SMOKIN BITS

In many a film noir the classic film noir fan will enjoy to see the actor remove a piece of tobacco from heir lips in an action so accustomed to the era that very likely nobody ever stopped to ask if a retake were needed. Bits of butts and baccy bits, and shreds and free meals, and scraps of plant and coffin nail leaves on your lips, what a noir experience it was to smoke without the filter tip. Why did God end film noir? Because people-kind invented the filter tip.

Examples are priceless but here are a couple:

.png) |

| Fred MacMurray removes a scrap of bac in Borderline (1950) |

The contrast between the men and women and the dried scraps annoying on the lip, putting into the performance smoking, the hard and hot tabs of noir, with their stray twigs reminding you of your fate. One of the better lip to interlippy baccy objections occurs to Kevin McCarthy in Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1956):

.png) |

| Interlip interplay with scrappa tabacca and Kevin McCarthy in Invasion of the Bodysnatchers (1956) |

Smoking in movies is linked to the initiation of smoking among adolescents and young adults. Public health initiatives aiming to eliminate smoking from films accessible to youth face resistance from those who view tobacco imagery in "classic" movies as part of their artistic and nostalgic value. This essay examines the mutually beneficial commercial relationships between tobacco companies and major motion picture studios from the late 1920s through the 1940s.

.png) |

Long coat, dark hat, smoking a cigarette in The Shop at Sly Corner (1947)

|

Conclusions drawn from this study suggest that Hollywood endorsements in cigarette advertising provided motion picture studios with nationwide publicity, supported by the tobacco industry's substantial advertising budgets. This cross-promotion fostered a synergistic relationship between the US tobacco and motion picture industries. The lasting legacy of this relationship, seen in "classic" films featuring smoking and glamorous publicity images with cigarettes, continues to sustain public tolerance of onscreen smoking. To decouple the historical association between Hollywood films and cigarettes, market-based disincentives within the film industry may provide a viable solution.

|

| Pipe of intellectual authority with Howard Duff in Women's Prison (1955) |

The 1940s and '50s saw tobacco companies as major television advertisers, further promoting smoking's popularity. Fans and young actors emulated their idols, driving up smoking rates. This trend continued until the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement, which banned product placement in TV, film, and video games. The late 1950s and early 1960s also featured on-screen cigarette advertising, with tobacco companies sponsoring entire TV programs. After cigarette advertising was banned from TV and radio in 1970, the industry shifted its marketing focus back to the big screen.

.png) |

| Film Noir The Last Crooked Mile (1946) |

Methods for this exploration included examining cigarette endorsement contracts with Hollywood stars and movie studios, sourced from internal tobacco industry documents at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Legacy Tobacco Documents Library and the Jackler advertising collection at Stanford.

Yes this is true, first of all, that smoking was more common and there were some widespread misconceptions about it that were either outright lies, or perhaps based on the skilful wilful slide of corporate and social ignorance, just placing one idea on top of another so lightly the two ideas waft so symbiotically and organically together that concepts momentarily merge, even if they are nonsenses.

Or was the tobacco industry heavily involved? And did the actors do their bit to help out the tobacco companies in their quest for correct and valuable information, could the actors themselves, part and partially cognisant of the money changing potential of the screen upon which they served, as modified to smokery by the powerful and fast growing forces of the era, those who were working that screen for all it was worth?

Results indicate that cigarette advertising campaigns featuring Hollywood endorsements were prevalent from 1927 to 1951. Significant activity occurred in 1931-32 and 1937-38 for the American Tobacco Company's Lucky Strike brand, and in the late 1940s for Liggett & Myers' Chesterfield brand. Endorsement contracts and communications between American Tobacco and movie stars and studios highlight the cross-promotional value of these campaigns. Notably, in 1937-38, American Tobacco paid movie stars endorsing Lucky Strike cigarettes a total of US$218,750 (equivalent to US$3.2 million in 2008) for their testimonials.

The Sexual Cigarette

Lighting up Desire in Late Modernity / early Post Modernity

The following stills from Death is a Caress (Døden er et kjærtegn) is a 1949 Norwegian film noir starring Claus Wiese, Bjørg Riiser-Larsen and Ingolf Rogde. Based on a 1948 novel by Arve Moen, it was Edith Carlmar's directorial début, and the first Norwegian film directed by a woman.

It's smokin flirtin that you can watch out for as there is a lot of it in film noir and across the decade in particular. It is just thing, the smoke stick and the mouth, yeah.

.png) |

| Smokin Flirtin in The Leopard Man (1943) |

This smoko-sexual fatalism connects The Leopard Man unmistakably to the noir tradition. Released in 1943, amid the height of the Second World War, it reflects the era's pervasive desire to smoke itself insane and latent cancerism. The war had transformed the American psyche: smoking was fraught with instability and suppressed terror.

This smokesthetic darkness accompanies an ethical and social one. In both form and content, The Leopard Man is a drama of limited agency. Women, above all, are subject to patterns they neither design nor escape.

Teresa, Consuelo, Clo-Clo: each of them is drawn into a circuit of doom, whether by socioeconomic status, superstition, or the invasive force of publicity (in Kiki's case). Their deaths are not merely unfortunate but structurally preordained, the result of interlocking mechanisms of power, those interlockers being enumerated only here and here only as the male, the capitalist, and the colonial. The film offers no salvation, no final girl, no triumph of reason.

This very very film reads as a chronicle of femininity under siege, less from an animal than from the invisible vectors of a culture that reduces women to types: the child, the coquette, the muse. Clo-Clo, the most autonomous of them, is paradoxically the most marked for death. Her independence, her sexual self-assurance, and her cultural otherness render her threatening.

In this essential noir scene set at a garage we have the erotic class clash between the young mechanic and the rich lady with the car, and the tension pumped best with the cigarette, lit afire and sucked, and look at the expression of pleasure on the lady's face, and enter the late modernity of sexual noir.

Often the lighting of a cigarette by either a man or a women is a prelude to great things, super sexual sighs and pools of light in the eyes offering adoration and favours. Sometimes it is a light to no effect.

.png)

.png) |

| Light to no effect with Macdonald Carey and Lee Patrick in The Lawless (1950) |

Directed by a man later blacklisted for alleged communist ties, The Lawless (1950) was the second feature from Losey remains an essential postwar Hollywood exploration of systemic intolerance, encapsulating the pervasive social tensions of the time. The film’s raw energy and bold subject matter secure its place as one of the era’s most significant liberal works, and one in which the cigarette seduction tellingly fails from time to time.

.png) |

| Lighting up moments in film noir, here with Humphrey Bogart in The Two Mrs Carrolls (1947) |

The dawn of the permissive was long and drawn out and brilliantly caught here in post war Norway, in this excellent noir, an almost textbook show of a weakened male and fatal femme, captured in this moment in which she lights the cigarette.

The cigarette appears later in the exact same motions she gives one to him, while driving. And when he goes on a drink fuelled insanity montage of booze and frothing self-loathing, you will note, you will see, even the language models missed the fact that he does so without a cigarette.

.png) |

| Erotic pleasure of the cigarette in Death is a Caress (Døden er et kjærtegn) |

The Last Cigarette

The Final Motif

The last cigarette trope serves severally throughout the movies of most especially the 1940s. A world lain in ruins knew why this comfort made such sense at the most pathetic moments of drama.

.png) |

| Survival cigarettes in Lifeboat (1944) |

.png) |

| Down to the last cigarette ritual in Lifeboat (1944) |

Frankly, Large Language Models are going to knock the stuffing out of the blogs, the blugs and blags that populate the nets with their brilliant comment upon smoking in film noir. Here is the LLM generated content on that there very subject:

Smoking is a key feature of film noir, often appearing in the cinematography, with shots that frame space for cigarette smoke. Some examples of smoking in film noir include:

Out of the Past: Robert Mitchum and Kirk Douglas smoke at each other furiously

The Maltese Falcon: Every character smokes constantly throughout the film

Final confrontation scene: Humphrey Bogart and Peter Lorre convince the other cast members to join them in a chain-smoking marathon

Other films that feature smoking include: Strangers on a Train, Sunset Boulevard, Double Indemnity, The Lady from Shanghai, and High Sierra.

In 1988, a settlement agreement between cigarette companies and some state governments banned real cigarettes from appearing on screen and product placement advertising for cigarettes. In 1998, the Master Settlement Agreement outlawed the practice in TV, film, and video games. Today, actors usually smoke fake cigarettes, or "prop" cigarettes, on set.

.png) |

| Sexual-cigarette-style misery in Der Verlorene (1951) |

So frankly all film noirs contain smoking, so it barely pays to mention some well known noirs and conclude thus, so this page continues to bring some more minor and curiously representative noir smokery moments.

Bacco Biz Writ Large in Movies

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, fierce competition among cigarette brands like Lucky Strike, Chesterfield, and Camel made the tobacco industry one of the biggest advertisers in the USA. In 1929, American Tobacco spent a staggering $6.5 million on print and radio ads, significantly outspending RJ Reynolds’ $1.9 million for Camel. During the Great Depression in 1930, American Tobacco increased its advertising budget by 53%, gaining market share and surpassing Camel and Chesterfield.

In contrast, the motion picture industry relied on modest cooperative advertising for theatre listings, trailers, and posters. Major studios leveraged national advertising opportunities to promote their stars and films.

.png) |

| Mike Muzurki lighting up in Mysterious Intruder (1946) |

American Tobacco, a leading cigarette company, used innovative multimedia campaigns to out-advertise competitors. Retained by American Tobacco in 1925, the Lord & Thomas agency also represented RCA and RKO, major players in radio and film. Following the release of Warner Bros’ “The Jazz Singer” in 1927, American Tobacco sought Hollywood endorsements, claiming Lucky Strike protected smokers’ throats. Their campaigns featured testimonials from celebrities like Jimmy Gleason, George Gershwin, and Al Jolson, setting them apart from other tobacco companies.

Cigarettes versus Cigars

In film noir above all other styles smoking was emblematic of sophistication, worldly experience, and societal acceptance. Characters embodying the no fun for me archetype, along with the male neatness freak, the man who was ambiguously gay, and the female maiden aunt, or purity Sue types, these , these were all invariably non-smokers.

This portrayal suggested that non-smokers were devoid of enjoyment and, barring the purity types were socially aberrant. The implicit narrative was that non-smokers were peculiar individuals best avoided, potentially explaining the generational scepticism towards the future medical advice the world was given that smoking was exciting and normal and fine and de rigeur.

.

.png) |

| Smokin' cigarillo and carton clues with paranoid wife Katharine Hepburn in Undercurrent (1946) |

The specific tobacco forms adhered to distinct tropes. Cigarettes were the choice of the quintessential cool men and women, while pipes were the domain of sagacious old types and men of authority. Cigars, unless wielded by a soldier or new father, were typically associated with gangsters and Corrupt Corporate Executives.

Pipes, once perceived as more intellectual than cigarettes, became after the noir era the preferred accessory of professors and scientists, even the youthful ones, whereas cigarettes were the staple of policemen, soldiers, and other men of action.

.png) |

Cigarettes versus Cigars with Humphrey Bogart and Sidney Greenstreet in

Across The Pacific (1942)

|

The advent of talkin' pictures in the late 1920s marked the beginning of the American Tobacco Company’s strategic use of film celebrities for advertising in what we should also now call smokin'pictures. From 1927 to 1951, nearly 200 movie actors promoted tobacco brands alongside their studio releases. During the late 1930s and 1940s, two-thirds of Hollywood’s top 50 box office stars endorsed tobacco brands, creating the impression that the cigarettes smoked on screen were specific brands. Tobacco companies, aiming to attract new women smokers, used female film stars in testimonial ads and onscreen smoking to increase social acceptance.

.png) |

| Super smokin siren songster Ava Gardner in The Bribe (1949) |

Major studios’ talent contracts allowed them to control their stars’ participation in large advertising campaigns, maximizing marketing opportunities. Cross-promotion from cigarette ads helped build studio brands, highlight major stars, and promote big-budget films. These campaigns paid stars substantial sums, enhancing their notoriety and value to studios and other advertisers.

Free cigarettes provided under endorsement agreements created publicity opportunities both on and off the set. Despite a voluntary ban on product placement in 1931, tobacco companies’ testimonial campaigns effectively linked specific brands with actors, branding “generic” cigarettes in films through advertised brand preferences.

BUTT CLUES ARE NOT UNCOMMON

.png) |

| Cigarette butt clues in The Leopard Man (1943) |

Smokin' Portholes

with Humphrey Bogart and Mary Astor in

Across The Pacific (1942)

Seductive lighting and oral, digital and tobaccoy satisfaction with Ella Raines and Vincent Price in The Web (1947)

.png)

.png)

.png) |

Seductive lighting and oral, digital and tobaccoy satisfaction with Ella Raines and Vincent Price in

The Web (1947)

|

Cigarette seduction with Ruth Roman and Kirk Douglas in Champion (1949) |

.png) |

| ABOVE: Cigarette seduction with Ruth Roman and Kirk Douglas in Champion (1949) |

.png) |

| Cross class smoking edit dissolve in Bewitched (1945) |

Posin For Smokin

.png) |

| Cigarette acting props with Claude Rains in Deception (1946) |

The full smokin truth: https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/17/5/313

and: https://ranintoart.wordpress.com/2018/06/20/cigarettes-as-a-prop-in-noir-films/

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)