Nazi business as usual is taken care of in traditional 1940s style. The great thing about this and the many other film noir / Nazi crossover propaganda films, is that the propaganda is nice and easy; it's never been more straightforward.

Our story in brief, attempts a few tales at once, some of which are muddied by the Nazi overacting and overkill. The models are nice, but they don't help the viewer, but it is pleasing to think that somebody had the fun job of making them. Even if we are supposed to consider that somewhere, there is a Nazi Department of Modelmaking; there to serve each division in each conquered European country.

Beginning in the quaintly, faintly ridiculous Norwegian fishing village of Trollness, which is occupied by the Nazis, the Norwegian flag is observed flying high over the town by a passing patrol aircraft. This patrol craft is of course fully equipped with World War 2 tech; including a notebook which lists all the countries that the Nazis now occupy.

Anyway, this flag is of course not allowed and theGerman troops sent to investigate discover that everyone in the village is dead, both German and Norwegian, including the German commander, Captain Koenig, in his office.

This is the dead bodies bit, and simply must be warned against. Nobody, not even in war noir, wants to see so many extras lying so still, all at once.

Heading into flashback, we commence the first proper tip of the hat to the film noir style, as our mystery unfolds. Previously, it turns out, the local doctor, Martin Stensgard (Walter Huston) and his wife (Ruth Gordon) wanted to hold on to the pretence of gracious living and ignore the occupiers. The doctor would also prefer to stay neutral, but is torn.

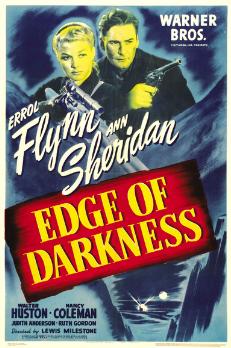

Kaspar Torgersen (Charles Dingle), his brother-in-law, the wealthy owner of the local fish cannery, collaborates with the Nazis, and so there is of course a little Trollness trolling to be achieved here. The doctor's daughter, Karen (Ann Sheridan), is involved with the resistance and is in a romantic relationship with its leader Gunnar Brogge (Errol Flynn).

Johann (John Beal), the doctor's son, has just returned to town having been sent down from the university but is soon influenced by his Nazi-sympathizer uncle. Karen makes it known to the townsfolk that her brother is a "quisling".

The key group of resistance members, headed by Gunnar and Karen, anxiously await the secret arrival of arms from an English submarine. They hide the delivery of weapons in a cellar and call upon the townsfolk to delay violence until the opportune moment.

Hooray! There will be no revenge today.

Karen's father leaves the meeting and bludgeons a German soldier to death which is a great move however, and just the sort of trolling you'd expect from a Trollness citizen. Captain Koenig orders the suspected resistance leaders to be shot. On the morning of their execution they are forced to dig their own graves in the town square. They hear singing and discover the townsfolk have armed themselves with the smuggled guns, grenades and other weaponry. The local pastor, who previously had called violent resistance "murder," opens fire from the church tower and the townsfolk follow suit. They successfully capture the port, and load the women and children onto fishing boats bound for England.

At the local hotel, which has been used since the occupation as German headquarters, the remaining soldiers prepare for the oncoming attack. Gunnar, Karen, her father, and the other resistance leaders and members make their way through the forest toward the hotel.

Karen's brother cries to them from the hotel that they are walking into a machine gun crossfire trap set by the commander. He is shot dead for his efforts by the Germans. After a bloody battle, the rebels eventually capture the hotel and Captain Koenig commits suicide after writing a letter to his brother.

The story then reverts to the newly arrived German troops finding the dead bodies of both Germans and Norwegians littered about the town, forest and hotel. They declare that there is no one left alive. Karen and Gunnar, up in the hills, see a German soldier taking down the Norwegian flag and replacing it with a Nazi one.

Karen shoots him dead and the Nazi flag falls on his dead body. Gunnar, Karen, her father and the surviving resistance members and townsfolk take shelter in the hills as the voice of President Franklin D. Roosevelt tells his listeners to look to Norway for understanding of the war and the hope and strength of the people.

And thus concludes one of the strangest war fables to ever grace the silver screen; a to-ing and fro-ing and at times quite slow meander through the horrors of a desperate occupation.

Of all its oddities, it is perhaps Errol Flynn who makes the least impression; which is a shame as he is staggering good looking. Curiously, though, this role as a resistance fighter against the Nazis was enough to have Edge of Darkness cited as definitely Eroll Flyn's most communist (ish) movie.

This is not Film Noir, we are afraid to say.

We know that Edge of Darkness is not film noir, because it is low on paranoia. Despite there being Nazis, and war, and suspicious villagers, there is no paranoia factor in Edge of Darkness. If anything, the Nazis are a little disappointing, not always very frightening, even if they have a tendency to shoot old men.

When the drama rolls in Edge of Darkness, it does so methodically and with anything at all, a stab at the flavour of Douglas Sirk; but this is the flavour of Lewis Milestone. Not only is there no paranoia, but instead there is Newtonian logic, or as is this is war time it is more like Val Lewtonian moralising; the characters often have to work out their values in speeches and discussions around values.

None of this is even remotely tinged with psychology and in Edge of Darkness, this is sorely missed, as it would have added something quite considerable. So no, we are not in noir territory at all, despite the odd signpost that we might be. The title of the film Edge of Darkness might suggest to many a hot dollop of noir, but there ain't none here.

No psychology, no paranoia, no camera shots at even slightly skewed or jaunty angles; a whole lot of model boats and village mountainsides, many model trees and cabins; precious few shadows and even further gaps between mood lighting and cigarette smoke. Even despite there being a village quisling, a traitor to the Norwegian people, there isn't even any back-stabbing double-dealing malice that might spice up an otherwise excitingly titled film such as this.

Do not get this wrong. The models are fantastic, as is the mis en scene, and Errol Flynn is handsome to silly degrees in his fisherman's garb.

Good old montage - - by Don Siegel!

I bet it was Don that piled up those bodies, that is all.