A man tumbles out of the door and slides and slithers down two flights of stairs and is stone-cold dead when he hits the bottom.

There now follows an hour and a half of flashback and flashbacks-within-flashbacks about a veteran returning from the war, tired and disillusioned, only to find that he girl he loves has lied to him about her relationship with another man, and that man she now cares about is sadistic and pretty much an all-round cad.

Although not one of the best known in the canon, the film noir credentials of The Long Night (1947) are supreme ― sublime to say the least. As well as featuring Vincent Price, warming up to become one of the great pantomime movie villains of the century, this was also Barbara Bel Geddes’ first film roles.

Then there is Henry Fonda ― superb to watch, even though he is not one of the crowned kings of film noir. Still ― he has plenty to offer here, in what we’d like to christen as the ‘sap-in-a-cap’ style of film noir acting.

Let the sap-in-a-cap flashback begin.

One of the most distinct aspects of film noir storytelling ― and one if its principal gifts in terms of what it offered directors and the filmmakers that have followed ― was the flashback style.

|

| Henry Fonda - - sap-in-a-cap in The Long Night (1947) |

This makes the flashback a key identifier of the fact we're watching film noir. It's psychological and it's personal, it is intimately subjective. And as if visiting the cinema was not enough of a remove, the flashback takes us further back, further away, places the viewers at a yet more extreme psychological distance.

|

| Vincent Price in The Long Night (1947) |

The flashback storytelling style is a hallmark of noir. It’s not like a romance or a musical, or a comedy, that takes neat and linear steps to audience satisfaction, promising a rising series of short climaxes, leading to a superbly happy ending.

Noir is often instead entirely flashback ― and The Long Night is one of the more perfectly engrossing examples of the form.

Flashback is noir’s way of changing the landscape, and altering the viewer’s mind in terms of what the experience and what they expect. Flashback was a captivating experience in the movie theatre, more unsettling than the relaxed feeling one might expect from a linear five or three act show.

Flashback is noir’s way of messing with the psychology of the viewer. At times, it isn’t even clear what you are watching, and the beginnings, ends and middles are confused, perhaps as they can be in the human mind. So once more, film noir pioneers its way into the dream landscape of the human mind, sometimes descending into the basement only to emerge from it into the light, and usually always

|

| Flashback and broken mirror in the film noir style The Long Night (1947) |

In retelling the events that lead the character to where she or he is ― in this case, Henry Fonda being shot at by the entire police force of his small town, while holed up on the top floor of a boarding house ― flashback cleverly unravels a story, winding sympathy and suspense out of nothing.

The technical term for this shift is anteriority, and its here in spades in The Long Night. In its most refined form, anteriority is marked in film noir by the voice over, with its most extreme and best known expression probably being found in Billy Wilder's Sunset Boulevard. What the voiceover does is mimic is the internal mental voice, and rather than presenting objective factual storytelling, immediately places viewers within the frame of subjective memory.

There is always a distinct defiance to every Henry Fonda performance, and he looks peculiarly modern, not old-school style like many of the more favoured noir actors. Humphrey Bogart and his like, the actors such as Burt Lancaster and Dana Andrews ― these guys wore hats ― fedoras to be correct.

|

| Henry Fonda in The Long Night (1947) |

|

| Vincent Price in The Long Night (1947) |

Henry Fonda in The Long Night is more than just a sap in a cap, however. True ― not all the time. There are several early sap-in-a-cap scenes, the first one being some burgeoning romance on the factory floor, when Barbara Bel Geddes as the flower delivery girl, makes one of life’s wrong turns and winds up sharing lunch break with the dynamic, optimistic, happy-go-lucky young worker.

Then there is sap-in-a-cap and the Teddy Bear, an emotional set of images that might not have worked so well with Burt Lancaster, Humphrey Bogart ― or any of many alpha males here portrayed in the world of film noir. Somehow, for Henry Fonda ― a teddy is not an issue.

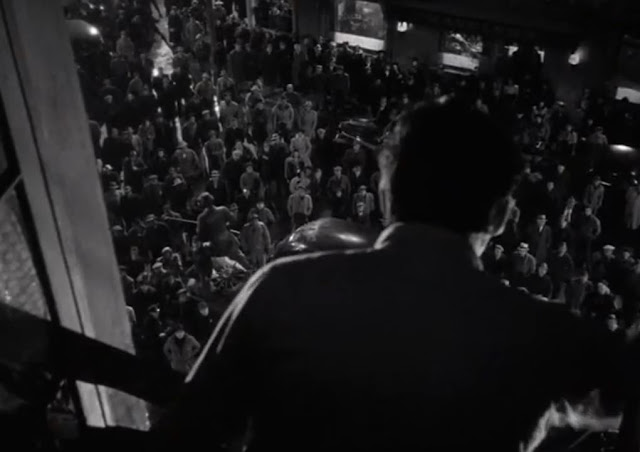

As well as the rather fun performances, the set design and artwork are worth of comment, in The Long Night ― the boarding house is amazingly crummy, and the small town exteriors are great, from the town square with its eager hordes of public gawkers, and the run down industrial corners, where romance is obliged to struggle like a weed out of the burned earth and advertising spaces.

But just because it is Henry Fonda ― there is something else, a factor you cannot find anywhere else ― and that is that working class heroism ― and his touches of popular justice, which works out so well because the bourgeois deceit and romantic fantasy ― as shown by Vincent Price as his character sells magic and falsehood to the world, and Barbara Bel Geddes ― only Henry Fonda can respond to this with justice ―with a look that would probably require a handgun in anyone else’s performance.

So as well as a film noir ― The Long Night (1947) is a Henry Fonda piece ― many of which are unique for these very unique qualities that he brings.

On top of this the heated exchanges he has with Vincent Price are terrific. And finally, and more worthy of comment is Ann Dvorak, who pulls off a brilliantly cynical performance. It’s a shame that Ann Dvorak here, or manybe nowjere else fits into the well-known femma fatal role. But here ― she is merely cyuncial, weary, broken, and not especially trying to harm anyone, not even in fact save herself.

|

| Crowds, sympathy, madness in film noir The Long Night (1947) |

|

| Barbara Bel Geddes in The Long Night (1947) |